This article is written for Evolving Wellness by guest author Marta Montenegro.

Whether you are currently or have in the past engaged in physical activity or played any sport at the professional, amateur, or simply leisurely level, your age is not the only factor to consider when it comes to your physical abilities. While age and genetics do play a role, it doesn’t mean you have to give up being active and the sports you love.

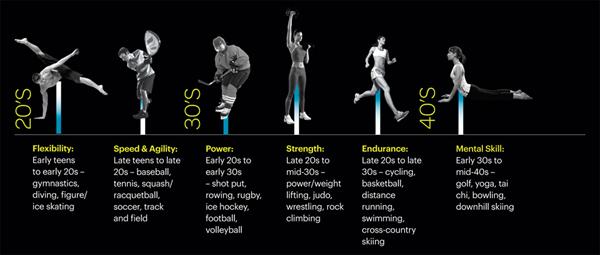

You may have missed the boat at your peak time to compete in a sport, but don’t throw in the towel yet. (Check out our energy table below to see which sport fits you best … at any age.)

It’s not necessarily your age that determines if a specific sport is more suitable for you, but rather the effort and time it takes to develop your body for that sport, as well as your personal dedication, overall health, prior training, fitness level and functional capabilities,” says Andy O’Brien, CSCS.

Sports and Exercise At Any Age

Physiologically, our capacity to perform at a certain level is limited by our chronological age. But don’t let that discourage you from taking up a new sport, regardless of the physical factors that dictate peak performance.

The key is to compete within an age-specific group or league. “Everyone shows different levels of decrement with age, yet we all have the ability to compete in age-specific groups regardless of how old we are,” says Joseph Signorile, PhD. Remember, age is just a number. As Signorile says, quoting George Bernard Shaw: “We don’t stop playing because we grow old. We grow old because we stop playing.”

Flexibility peaks in late teens and early adulthood. At this age, body mass and percent body fat are relatively low, providing a good strength-to-body weight ratio. Optimal flexibility, smaller stature and a good strength-to-weight ratio are advantageous in sports such as gymnastics, which require extreme ranges of motion and rotating/spinning in the air.

Speed and agility sports, where the resistance is one’s own body weight, require a high degree of sports-specific coordination and a high amount of strength per unit of body weight. In the late teens and early 20s, motor skills are well developed. At this age, strength approaches peak levels, and percent body fat levels are relatively low. The relatively high strength-to-low body weight ratio is advantageous in sports requiring speed.

Power, or explosiveness, requires a quick display of force rather than just a display of maximum force. Strength (which peaks from mid-20s to early 30s) is undoubtedly important, but success will depend on the rate at which force is developed. Peak power in a sport requires years of skill or technique training and explosive resistance training, which mimics the sport movement and significant strength development. These three factors often come together in the mid-20s and early 30s.

Endurance sports require mental focus, superior aerobic capabilities, optimal physiological efficiency (or economy) and a high threshold for the onset of lactic acid accumulation. While aerobic capacity can peak in the early 20s, prolonged endurance training can improve efficiency (or economy) when performing a task.

Elite distance runners, for example, use a relatively low amount of oxygen when running at a given speed. Also, they can run at a high percentage of their aerobic capacity. The combination of improved mental focus, improved physiological efficiency/economy and increased threshold for lactic acid accumulation explains why runners continue to improve their performance into their 30s despite achieving their aerobic capacity early in their training.

Mental skills, including focus, confidence, strategizing and patience, can continue to develop beyond the 30s. In some sports, athletes can compensate for losses in strength and stamina by gains in strength and skill.

Physical Factors

Apart from your training regimen, there are also physiological changes that favor the younger athlete across a lifespan. If you maintain a solid and consistent training routine between the ages of 14 to 25, you have a greater chance of peaking at your optimal genetic capacity to compete in the sport of your choice. Here’s a list of physiological groups to help you refine your skills and train for any sport.

“Although we are able to teach an old dog new tricks, the process of learning a sport later on in life is much more time-consuming and requires patience, practice and a lot of training. But it can be done!” says Sandler.

Flexibility: Early teens to early 20s – gymnastics, diving, figure/ ice skating

Speed & Agility: Late teens to late 20s – baseball, tennis, squash/ racquetball, soccer, track and field

Power: Early 20s to early 30s – shot put, rowing, rugby, ice hockey, football, volleyball

Strength: Late 20s to mid-30s – power/weight lifting, judo, wrestling, rock climbing

Endurance: Late 20s to late 30s – cycling, basketball, distance running, swimming, cross-country skiing

Mental Skill: Early 30s to mid-40s – golf, yoga, tai chi, bowling, downhill skiing

Data provided by a collaboration of experts: Andy O’Brien, CSCS, Panthers strength and conditioning coach; David Sandler, CSCS*D, sports performance enhancement trainer for StrengthPro; Joseph Signorile, PhD, professor of exercise physiology at University of Miami.

About the Author

Marta Montenegro is a Venezuelan-born journalist, she is the founder, publisher and Editor-in-Chief of the award-winning SOBeFiT Magazine. She holds two master’s degrees — one in finance and one in exercise physiology — and is an adjunct professor at Florida International University, where she designed two new courses for the college. She is also a certified fitness trainer, a strength and conditioning coach, and a nutrition fertility lifestyles specialist.